Could ‘Cultivated Steaks’ Be the Future of Meat?

Food Tech

Asif talks with Aleph Farms CEO Didier Toubia about sustainability, kosher laws, and more

In the past, animals were domesticated for labor and meat; today, Aleph Farms’ CEO Didier Toubia claims to be domesticating meat itself – in other words, breeding steaks without a cow, and what’s more, with neutral greenhouse gas emission and minimal resource consumption. Could this be the answer to global warming? In an interview held at Asif’s test kitchen, we discussed the technology behind this cultivated steak, the role the company hopes to play in food security, and what the Rabbinate has to say.

Matan Choufan: On your website, you talk about “cultivating quality steaks.” Can you explain what that means?

Didier Toubia: At Aleph Farms, we learn from nature how a steak is produced inside the cow’s body. Today, we can isolate these cells, transfer them to a controlled environment (outside the cow’s body) and encourage their distribution so that they grow into a “steak.” This external process takes 3-4 weeks, as opposed to the 2-3 years it takes to grow a cow for slaughtering. This process is of course antibiotic-free, carbon-neutral [carbon emission is one of the destructive environmental effects related to cattle breeding], and free of animal cruelty. We could say we are domesticating steak, just like in the past animals were domesticated for food, but in a more sustainable, less resource-intensive way.

In a sense, we see cultured meat as an equivalent to hydroponics. Hydroponics uses the same seeds and reaches the same results in a different method. We, too, use the same cells and eventually end up with meat. In hydroponics, there is no need for pesticides as vegetables and fruits are grown in a controlled, soil-free environment. We grow cow-free meat.

But what is the meaning of “growing” here? Are you using 3D printing technology?

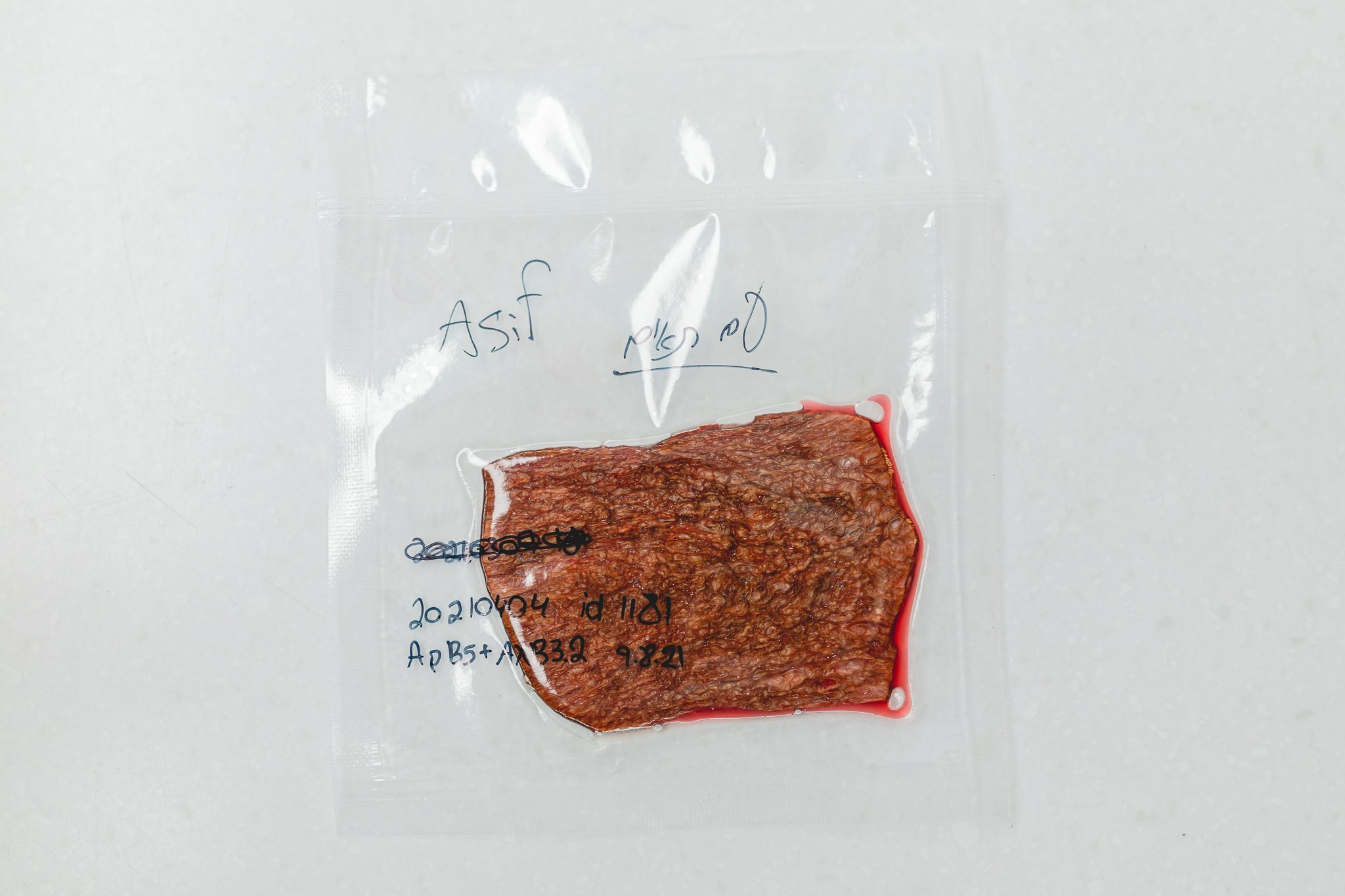

Our initial product is not a printed product. We imitate a matrix, a module simulating plant-based collagen [protein] network. This is the only component that is not derived from animal cells. On day zero there is a matrix (module) with a few cells attached to it, and in four weeks’ time, they multiply, grow, and create a complex tissue.

What’s the first product Alef Farms will launch?

A thin steak, low in fat and rich in proteins, with a minimal plant-derived component (the protein network/matrix). I expect it to be easily incorporated into the Mediterranean kitchen, which may be too broad a definition that we need to further develop. In general, we keep asking what cultures we can fit into. Meat is a very emotional issue; it is the center of the plate, and different cultures have different approaches. We must understand how we can fit into each culture.

It seems that developing a ribeye steak is a chief goal for Aleph Farms. Why did you choose this cut?

We developed two platforms for manufacturing steaks. The first, as we had described, is based on a support, a scaffold, or a module to replace the extracellular matrix because in nature cells must attach to the matrix to form a complex tissue. The second platform allows us to produce thicker steaks, such as a ribeye, with better control of fatty marbling —that is done with 3D bioprinting. We do not focus on one platform or the other; we invested in the two of them because our goal is to develop a wide selection of products and solutions that will answer a wide spectrum of user demands and needs and will fit into various cultures around the world.

What other cuts of meat do you have in the works? Will you ultimately develop meat from other animals, too? Will there be ground meat and does culture meat behave like regular meat when you cook it?

As this is cultured meat, we have complete control over the entire growing process. We can control the maturity level of muscle fiber, the level of collagen, the amount of fat — the qualities that change across different cuts. Theoretically, we can produce everything. In practice, we view cultured meat as another category of meat. We do not want to imitate specific cuts, but rather develop products with a unique signature and a unique value proposition. Just like we have red wine and white wine, two kinds of wine, we believe that 10 years from now we will have two kinds of meat: meat from a slaughtered animal and slaughter-free meat. Each will have its own value proposition. As for other kinds of animals, yes, this is something we plan for the future. Some of our products will be grindable, but our initial strategy is to focus on premium products, and that is why we decided to start with a beef steak. Will it be possible to grow meat for long cooking? Yes, absolutely.

In an interview with Bloomberg, you said that “food security should be a critical issue for collaboration, especially in the Middle East and Asia. We see Aleph Farms and cultured meat as a potential cornerstone of more food security in those two regions.” How can your technology assist here?

In two respects. Cultured meat uses a minimal amount of natural resources. For instance, we reduce water use by 50 percent and land requirement by 90 percent and use far fewer nutrients. In addition, cultured meat, unlike beef, can be grown anywhere: the climate of the Emirates, for instance, is not fit for raising cattle for slaughtering. In Asia, there is not enough land and water to breed cows. But we can grow cultured meat in these areas, so that cultured meat may become a local product anywhere, anytime. In this way, we can provide local populations access to quality nutrition, and reduce dependency on imports and on long-distance transportation of meat.

Furthermore, the production of cultured meat has a lesser effect and smaller dependency on climate. Today we are trapped in a vicious cycle in which the food system affects the climate and climate change affects the ability to produce food. In the U.S. and in Europe we see floods, heatwaves, fires, water shortages. Climate change prevents us from producing food in the way we used to. Cultured meat is resistant to climate change, and therefore may be a solution that will enable humanity to continue to produce high-quality nutrition.

In addition to the economic and ecological significance of reducing import dependency, cultured meat also has geopolitical implications. We see more and more countries wishing to increase their food independence. China, a heavy meat consumer, imports 90 percent of its beef. With the trade war being waged under the Trump administration, Australia became China’s largest supplier. Three or four years ago, China also began purchasing farms around the world, to ensure its population’s access to meat.

So, the importation of food in general and meat, in particular, is a highly strategic issue, and cultured beef can foster cooperation with our neighboring countries, supporting political stability in the Middle East. To me, this is bigger than food and nutrition.

On the other hand, this is a rather expensive product.

It depends. Innovative products tend to be pricey in the beginning and become more accessible with time. Think about laptops in the early days, digital cameras, solar panels. Cultured meat is expected to see a similar cost curve and customer price curve. At first, it will be relatively expensive, but as we scale up manufacturing, customer prices should go down. We have a clear plan to match our prices to those of meat from slaughtered animals within five years of the initial market launch. This is significantly shorter than other products, in particular plant-based meat substitutes, which usually take about 10 years to reach price parity.

You plan to introduce your product to the market at the end of 2022, depending on regulatory approval. Who are your initial target customers? Restaurants and chefs? Butchers? Home cooks?

We plan to start by working primarily with chefs, in order to promote Aleph Farms’ unique food culture. Food culture isn’t created in supermarkets; we will enter retail chains later on. On a side note, it seems the most likely customers for cultured meat are carnivores, not vegetarians or vegans. In our surveys, Generation Z appears to show the highest interest in our product – 90 percent in countries such as the U.S. and UK, and about 80 percent of the general population.

As a follow-up, how did the Coronavirus pandemic affect your go-to-market strategy, considering the significant impact of COVID-19 on the restaurant industry?

The pandemic affected us in two ways. On the one hand, it accelerated processes supporting the transition to a greener, more sustainable economy, a phenomenon that benefits us, as we were already highly invested in sustainability before COVID. It accelerated a trend that has been around for a few years, raising awareness in policy setters and individuals alike. Today, countries are more interested in establishing their domestic food security.

The second aspect is related to our interaction with customers and to the culinary concept we develop together with chefs and restaurants. This has undoubtedly become trickier with COVID, yet restaurants are not about to disappear, and the same goes for the role chefs play in our culinary culture. After each shutdown, we witnessed long lines outside restaurants. Everybody went back to eating out. This is something that is deeply rooted in our culture, and in our culinary culture in particular. The industry may have been affected temporarily, but it will recover, it already has. Beyond the physical restaurants, chefs develop new models for interaction with customers, and I believe that just as the restaurant world adjusts to the new reality, so will Aleph Farms.

Regulation on cultured meat is relatively new and is perhaps still taking shape. How do you approach this and what are the challenges?

I think that if two years ago the regulatory framework was unclear in many countries, today in most of them, including the U.S. and Israel, the regulator has studied the topic. I do not see regulation as a barrier to market entry. Still, it is very important for us to assure both the quality and safety of our product and so we perceive the mutual work with the regulator as a training or a process that can help us to improve even more. At the moment, we are involved in various processes in multiple countries, including Israel, of course, to promote approval for the marketing of cultured meat. We will see more and more such products entering the market in the next year or two years.

Speaking of safety, what is the product’s shelf life?

“The product is grown in sterile conditions, so there is no fear of listeria or salmonella. As there are zero pathogens to damage it, it can potentially be preserved for longer. As this is still meat, biochemical processes will eventually make it go bad; but in general, the product has a longer shelf life.

Kashrut can also be considered a form of regulation. Is your product considered kosher?

“There is no inherent reason why cultured meat should not be kosher. As there are no such products at an industrial scale at the moment, there is no kashrut certificate issued by any kashrut supervisors or the Rabbinate. We work in full cooperation with leading halacha scholars (poskim), mainly in Israel, to assure our production methods comply with kosher requirements. We also make sure it will be halal. The kosher meat market in the US is evaluated at $26 billion a year. The halal market is even bigger.”

For meat to be kosher, it must be free of blood. Does your product contain blood?

We replace blood with a growth medium, a sort of blood we compose. It is not blood taken from an animal, it is a solution containing all of the blood’s basic components, but it is not animal-based. And yes, this is the main question: Can meat be kosher without slaughtering? Can the two be separated?”

Assuming the product will get a kosher certificate, do you think it will be considered “meat” (b’sari) in terms of Jewish law?

This issue is still being debated. The decision whether cultured meat should be considered b’sari or pareve [neither meat nor dairy] is highly significant, not only in the context of mixing meat and milk. If it’s pareve, it means we can also produce meat from non-kosher animals, and this meat will be considered kosher. As technically our product is meat, as opposed to plant-based meat substitutes, we assume it will be considered b’sari. Of course, I am not a rabbi, I am just making assumptions based on my analysis.

One of Aleph Farms’ goals is to reach zero carbonate emissions by 2025. Can you tell us a little about that?

Today, we humans eliminate our natural resources at an accelerated pace, and it is urgent that we start managing them otherwise. The question is not how to feed 9 billion people in 2040; this is a misleading question, as it allows us to believe we do not have a problem right now — and who cares what happens 20 years from now? We must understand we are facing a huge problem in the present. We see climate change intensifying year after year. Greenhouse gas emission is a major cause, and 30 percent of it is generated by the food system. Animal breeding accounts for half of that, and 7.8 percent of that is beef. This is much more than the entire worldwide transportation emission combined.Fixing the food system is the keyAs far as I know, Aleph Farms was the first and the only company to commit to being carbon neutral.

In general, cultured meat is part of a movement of returning to restorative, sustainable agriculture [like organic agricultur], as opposed to intensive industrial agriculture controlling the market at present. We believe it is important to raise cows and animals – this may sound provocative coming from the CEO of a manufacturer of cultured meat, but we need animals for land recycling and restoration. In intensive farming, the soil cannot absorb the carbon released into the air and recycle it in an optimal way. We must restore the required biological diversity and bacterial load (plants, insects, and bacteria) that should be in the soil. One method is using carbon sinks for absorbing carbon dioxide. At the same time, we must move to food production systems that are greenhouse gas neutral. Such a system can create a balance between nature and man, and generate enough food to feed the world without destroying it. This should be done with a focus on high-quality nutrition, of course, as industrial food is usually relatively low-quality.

Let’s talk frankly – cultured meat, too, is an industrial product.

This is a complicated issue. Cultured meat is an industrial product, but it is also a high-quality product. It is not an ultra-processed food, like snacks or sweets. It’s not processed meat like sausages, which contain very high levels of sodium. We are industrial, but with a focus on healthy nutrition.

You formed a division aimed at finding solutions for problems your product might raise, such as its effect on the cattle breeding industry. This is an uncommon strategy for a commercial company. Can you talk about your motives?

At Aleph Farms, our goal is to solve problems. To do this, we need the cooperation of our surrounding ecosystem. Farmers play a crucial part in our food system: they take care of the soil, which is the basis for all food. Healthy soil is the key to a healthy world, and farmers are hard-working people who sometimes do not get the credit they deserve. They are often victims of the system. Cultured meat may be described as cellular agriculture, so it is part of agriculture. As we have said, it is about the domestication of meat, the next step in animal farming.

We view farmers as partners. Cultured meat is a necessary complement for sustainable agriculture. We work with various farmer organizations to strengthen this connection, which is particularly important in Israel nowadays with the debates about the country’s agricultural future.

Israel has no comparative advantage in traditional agriculture: land here is scarce, and water is expensive. This is why we must focus on innovation. We have become one of the world’s leading countries in hydroponics, and we can achieve an advantage in cultured meat, too. I hope farmers will become involved in what we call “the hydroponics of meat.” I think it can be part of the solution for Israeli agriculture and contribute to improving Israel’s food security.

Devra Ferst contributed research to this story. This article first appeared in the Asif Journal

Tech Ecosystem

Tech Ecosystem Human Capital

Human Capital Focus Sector

Focus Sector Business Opportunities

Business Opportunities Investment in Israel

Investment in Israel Innovation Diplomacy

Innovation Diplomacy Leadership Circle

Leadership Circle Our Story

Our Story Management Team

Management Team Careers

Careers